Despite decades of failure talks and negotiations, the Turkish and Greek neighbors have no other option but diplomacy to solve their decades-long dispute. Last week, on May 26-27, Turkey and Greece virtually held a confidence-building meeting. Meanwhile, Turkish and Greek experts met, on May 25-28, in the Turkish Province Edirne, to discuss the land borders between Turkey and Greece. This is the fourth round of talks between Athens and Ankara, since the resumption of their talks, in January, over maritime disputes in eastern Mediterranean.

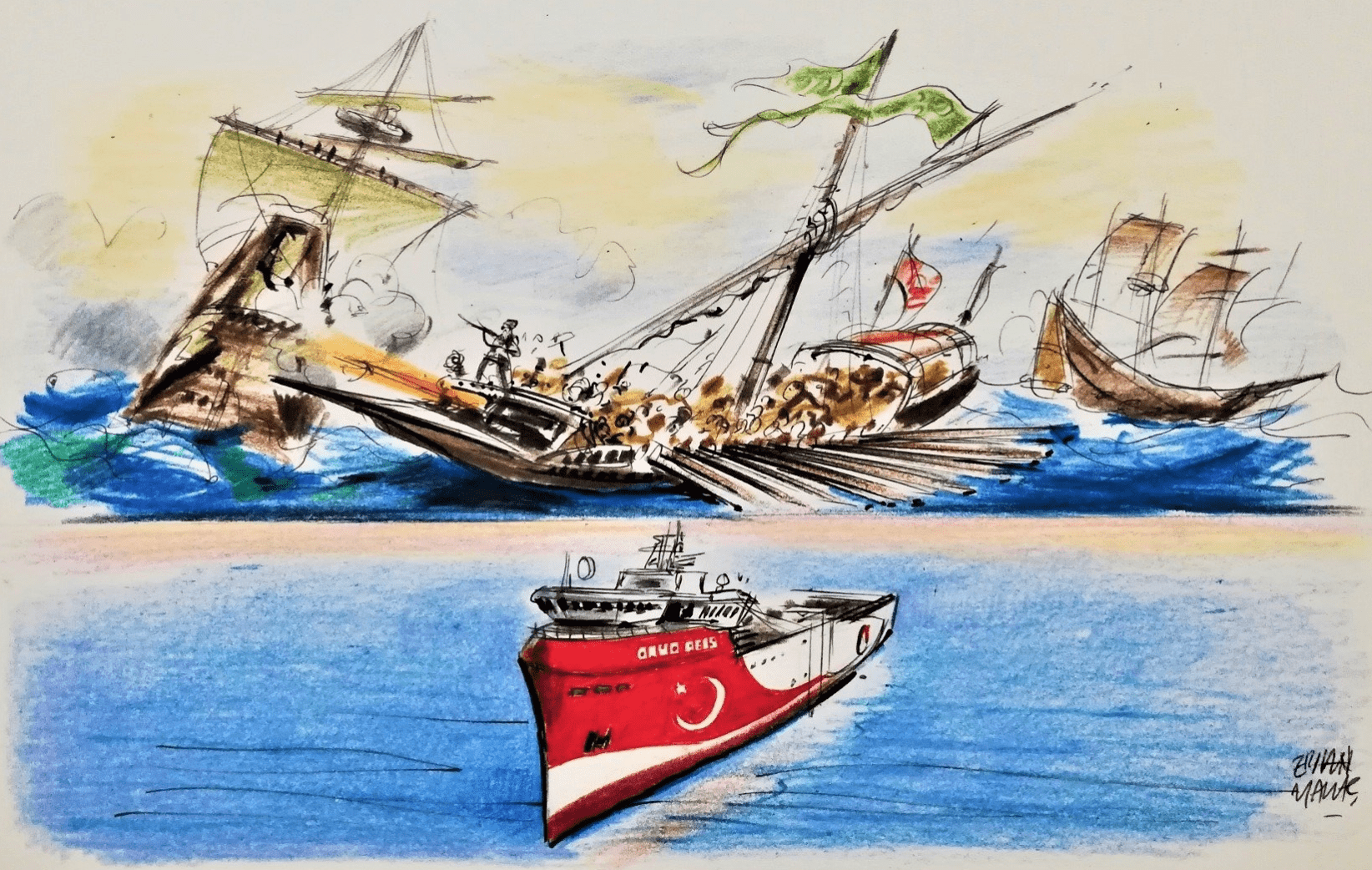

The resumption of exploratory talks between Turkey and Greece, in January, came after five years of boycott that were concluded by heated six months of military tensions in the eastern Mediterranean. In July 2020, Turkey, which apparently got bored with the slow-by-nature diplomatic channels, decided to sail the seismic research ship “Oruç Reis” in the disputed waters between Turkey and Greece, in search for natural gas. The move came after a few months from signing a maritime agreement between Turkey and Libya, that crossed the disputed maritime zone between Greece and Turkey.

As expected, Greece felt threatened by Turkey’s move, and thus decided to push back. First, it signed a maritime agreement with Egypt defining the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) between the two countries in the Mediterranean. The area defined in the Greece-Egypt agreement crosses the area drawn in the Turkey-Libya agreement and thus made it useless. As a result, Greece and Turkey started to mobilized warships, submarines, and helicopters against each other in the Mediterranean and the Aegean. In no time, the Mediterranean turned into a war zone with foreign naval and aviation forces coming to the Mediterranean to support either side of the conflict, under the guise of running joint military exercises.

This crazy scene has not stopped unless, in December, the Democrat Joseph Biden was announced the new president of the United States, after a brutal electoral battle against Trump. Biden does not hide his dislike to the Turkish President Erdogan and his bias to Greece and Cyprus in their conflict with Turkey in the Mediterranean. In the same time, the Government of National Accord (GNA) in Libya, which signed the maritime agreement with Turkey, was substituted by another temporary government. Only then, the two conflicting parties found themselves obliged to put their weapons aside and sit for talk.

The current round of talks between Turkey and Greece is the 62nd, since 2002, to discuss the extent of Turkey’s continental shelf and the demarcation of an EEZ between Turkey and Greece. Even during the heightened military tensions between Turkey and Greece, last summer, some technical talks were held between the two militaries. However, all these rounds of exploratory talks, technical talks, and confidence-building talks have not resolved anything. This was clearly reflected by the live verbal fight that erupted between the Turkish and the Greek foreign ministers, during the press conference that followed their one-on-one meeting, in April, in Ankara.

One can hardly be optimistic that the current talks between Turkey and Greece may lead to any practical solution. The reason for this is that the core of the conflict has never been addressed. The core of the conflict is not about the delamination of EEZ or maritime boundaries. It is about Turkey’s growing need for natural gas as the main energy resource to satisfy its needs. Natural gas is a matter of life or death for Turkey, which consumes a budget of 50 billion dollars per year to import from Russia, Iran, and Azerbaijan.

Turkey is the country with the longest borders in the hydrocarbon rich Mediterranean, but still it cannot search for gas there because a 1920s agreement that was signed under the fog of war. For decades before 2002, Turkey rarely disputed the Lausanne Agreement. But the discoveries of natural gas in the sea motivated Turkey to push for its rights in the seabed resources. This also motivated most of Turkey’s moves, in the past decade, in North Africa and the Middle East, too.

This year, most of Turkey’s natural gas contracts are either ending soon or has already ended. That includes its long-term gas contracts with main suppliers like Azerbaijan and Iran. In addition, Turkey’s ongoing military battles against PKK in northern Iraq and in northern Syria, are causing tensions with Russia and Iran, which may affect the renewal of gas contracts with them. Meanwhile, Turkey has been excluded from the EastMed Gas Organization, since it was founded in 2019. As a result, Turkey may resort to repeating the noise that took place in the Mediterranean, last summer. That would be a setback, not only for Turkey-Greece relations, but also for Turkey’s relations with everyone else in the Mediterranean and North Africa region.

To avoid another hot summer in the Mediterranean, the core of the problem should be addressed by all concerned parties, on the regional and international level. The core of the issue, here, is to come up with a solidarity arrangement or a fair solution that helps Turkey satisfy its huge need for natural gas, as its primary resource of energy. Regardless of other countries’ favoring or dislike of the Erdogan regime, there are more than 82 million Turkish citizens, plus more than four million refugees, who must be taken into consideration, when looking at the issue.

Be the first to comment